The

idea floated recently that CBC change from a

broadcaster to a

content company is just one of many that would ultimately see CBC abandon traditional broadcasting and focus on the internet. The internet is so cool and sexy CBC (and many other broadcasters) have never been able to resist its siren call in favour of old-fashioned, stodgy broadcasting; many a career within CBC has been made promoting dreams of internet domination.

Recently the CBC has taken to streaming exclusive content on the internet and has put increasing emphasis on other digital and internet-related media. This risks diverting the CBC from its core mandate, which is to serve all Canadians, not just the digital elite. It's very smart to use the internet as a complement to cable and satellite to distribute CBC radio and TV programs that already air on CBC's main channels. The CBC radio app is a wonderful tool allowing one to listen to their local CBC radio station anywhere in the world. But trying to compete on the internet with exclusive internet content is the broadcast equivalent of playing Loto 649.

For example, CBC

boasts that cbc.ca is the number one "Canadian broadcast media" web site but this ignores the fact that other web sites owned by Canadian broadcasters are not the competition. The competition on the internet is Google, Microsoft, Facebook, CNN, the BBC, the Globe and Mail, all the other Canadian and foreign newspaper sites and the thousands of other sites not owned by Canadian broadcasters. According to comScore, news web sites

account for less than 5% of internet use and cbc.ca has only a tiny fraction of that 5%, which pales by comparison to CBC's audience share of the radio and TV market. 5% amounts to only about 30 minutes per week for the average Canadian and Canada's broadcasters and newspapers and all the world's major news outlet are dividing up this 5%. cbc.ca, the Globe and Mail, the Toronto Star, etc. all face the same competitive dilemma, making the challenge of developing an internet content strategy a Herculean task.

How can the CBC ensure that an internet, or radio/TV, service is a valuable use of its (our) resources? Well, CBC must first return to basics and understand what public broadcasting is. There are two key features of

public broadcasting. First, public broadcasting is paid for involuntarily by citizens, either through mandatory licence fees or direct government funding. Citizens don't have a choice to pay or not to pay, as they do with pay TV, cable, etc. Second, the audience for public broadcasting must be substantial enough to warrant spending public money. Independent audience surveys must demonstrate whether there is a substantial segment of the population being served. Without the latter, there can be no accountability for the use of public funds. The audiences for many of the CBC's internet services are not measured by an independent, third-party, such as BBM or comScore, precisely because they may be serving a limited, perhaps unmeasureable audience. I refer here to services such as

CBC Music.ca and the recently launched

Hamilton 'digital' CBC station. Unless they are measured by a legitimate audience measurement service, no one, including CBC, will ever know if they are successful or should be funded continuously.

Our ten-year study of media use has demonstrated that old-fashioned TV

viewing levels are as high today as ever and that internet use (web surfing, email, Youtube, etc.) has stabilized at roughly half the levels of TV. Our studies show that radio too still maintains its place in the media hierarchy. This is not likely to change for many, many years.

Yet the CBC seems to believe the old TV/radio model is broken. The

analogue world of broadcasting has been replaced, they believe, by a new

digital world that allows viewers in particular to watch a program anywhere, on any screen (TV, computer, smartphone, tablet), at the time of their choosing. They believe viewers are now in control, not broadcasters, and they can watch a program stored on their PVR or their smartphone at a time and place of their choosing.

To quote a former head of CBC English TV and radio: “Appointment television and radio, consumed watching a screen or listening to a radio in the house is finished (My note: listening to radio in the house was finished ca. 1965). Now shows are available everywhere, whenever and however the participants want them. Distance and time are abolished. The days of being bound to a particular television show at 8 p.m. on Thursday nights are over.” Technically, this is true but it misses a quintessential aspect of radio/TV/movie storytelling.

Show business depends on generating a buzz for a new movie or TV series. Interest in a new movie is created by intense pre-release publicity and promotion leading to a launch on a chosen day, creating a desire to be among the first to see the movie the day it’s released or soon thereafter. TV programs are similar. Studios and networks don’t want people to store the content and watch it whenever they want on their phone, they want to capture the audience in the moment on the silver screen or TV set. No better example of this is the new Kiefer Sutherland

series, Touch, which aired to a world-wide audience in some 100 countries the same day, coincidentally on a Thursday night, creating a real time viewing experience across continents.

CMRI's Media Trends Survey has tracked usage and attitudes toward Canadian media, TV, radio and the internet, for the past ten years. Elsewhere we have examined

why people use radio. But what do our surveys tell us about how and why people use TV and the new media devices like smartphones?

One important thing we have learned is that only a relatively small cohort of people exercise the technical ability to watch programs when they want, that is, on a pay-per-view or on demand basis. For example, less than 1 in 10 people over the past ten years indicated that they order pay-per-view movies or events with any kind of regularity; this has changed very little over the decade. Another 1 in 5 order PPV rarely and some 7 in 10 never do so.

For the past 6 years we have asked people about the likelihood of using video-on-demand.

Once again, less than 1 in 10 people say they already use VOD and small numbers say they will likely do so in the coming year.

The overwhelming majority simply indicate they are not likely to exercise the ability to watch programs (usually for free) at the time of their choosing.

I suspect most people use VOD only when they can’t possibly watch a show when it is broadcast.

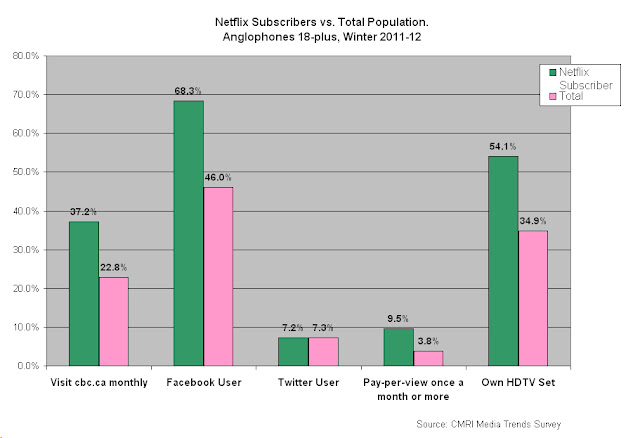

There is unquestionably a segment of society who are cutting edge and who can afford and use all the benefits of the newer technologies, including video on demand, videostreaming, PVRs, mobile TV, etc. However, it is small cohort of digital elites in relative terms and is unlikely to become a majority in our lifetimes.

On the other hand, TV for the everyman is a universal phenomenon and its most salient feature is that it is ‘here and now’.

Thus, when we have asked Canadians if they usually just turn on the TV and look for something to watch, we find remarkably strong agreement, which, if anything is stronger the past few years. 3 in 4 people agree that they just want to relax, turn on the TV and see what's on.

Finally, since 2006 we have tracked cellphone/smartphone usage and the results are very telling. Yes, roughly 3 in 4 Canadians now have a cellphone or smartphone and more and more people use it to text and send photos but less than 1 in 10 download music or video with their mobile device and there is scant evidence that downloading music/video to your phone is considered important or likely to grow.

People, for the most part, want to partake of TV at home on a primary screen in real time, not delayed for days or even hours. And I am not referring to just news and sports, which will always be real time programming. Most of TV (and radio) programming is here and now.

The internet, new digital media, especially mobile devices, are important but are an adjunct, serving to promote and enhance the core TV/radio experience. Only a small, elite proportion of Canadians will consume media in the way envisioned by journalists and others who

proselytize the new technology.

If an all digital, internet-based CBC were ever to be pursued, broad Canadian support for public broadcasting would dry up, the raison d’etre of CBC would disappear and the calls for the privatization or closing of CBC would intensify. CBC should experiment with new media and the internet but always remember that its core business is broadcasting for all Canadians, not just the digital elite.

The Media Trends Survey has been conducted for ten consecutive years and has surveyed over 15,000 Canadians in total in this period. It is the only survey to have measured media use and attitudes continuously over this decade. The Media Trends Survey is not sponsored by any one industry or affiliated with a media company. Therefore, the surveys are scrupulously designed not to bias respondents into favouring one medium or media outlet over another.